The Goins Hotel: A Hidden History of Black Success and Resilience in Columbus, Indiana

Progressive Preservation Talks: Goins Hotel Edition | February 17, 2026

By Black History Month Columbus

Last Tuesday evening, community members gathered at the Columbus Area Visitors Center for a special edition of Landmark Columbus Foundation’s Progressive Preservation Talks, focused on one of the city’s most significant—and deliberately hidden—pieces of Black history: the Goins Hotel.

Presented in partnership with Black History Month Columbus at the Columbus Area Visitors Center, the evening featured research from Paulette Roberts, who has been collecting oral histories and primary research on Black heritage in Columbus since the 1980s, and Cameryn Kent, an undergraduate intern at Landmark Columbus Foundation who deepened that foundation through secondary source research and visual reconstruction. Together, they brought forward the story of a building that served as a lifeline for Black travelers and a community hub for Black residents in Columbus during segregation—a story that was intentionally kept out of public view.

A Safe Place to Get a Room, Rest, and Eat

The Goins Hotel operated from 1928 to 1946 at a location above local storefronts at address 4th Street. It had 23 rooms, a small side entrance, and no signs visible from the street. It was never advertised. It operated entirely by word of mouth. It was not even listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book, the widely used travel guide published starting in 1936 by a postal carrier from New York to help Black travelers find safe lodging across the country.

Paulette Roberts described the presentation’s central goal: “The main focus was to allow the audience to put themselves back in time to understand and realize how Blacks were treated during segregation and the main reason was to let people know that there was a safe place in Columbus, Indiana for them to get a room, rest, and eat.”

To ground that understanding, Roberts used a visualization exercise during the talk. She asked audience members to close their eyes and imagine moving from one place to the next without being humiliated, ostracized, called names, or blocked from reaching their destination. That exercise put the Goins Hotel’s role into sharp focus: in a country where Black travelers could not count on basic safety or dignity at most establishments, Elmer and Lydia Goins built a place where people could rest.

Roberts’ commitment to this work is rooted in her own family history. She grew up in Hazard, Kentucky, in rural Appalachia, nearly three hours from Frankfort, where her father participated in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1964 March—a march that led to Kentucky becoming the first southern state to pass a civil rights bill. Roberts is also a descendant of an enslaved woman named Harriet, who, like many enslaved people, was not given a last name and took the surname of her enslaver, becoming Harriet Combs.

Roberts’ research includes firsthand accounts from people with direct ties to the hotel. Among them is Alan Smith Sr., a current resident of Columbus, who stayed at the Goins Hotel as a child. That detail landed especially hard with the audience—a reminder that this history isn’t centuries removed. Someone in our community experienced this place firsthand, just decades ago.

The Couple Who Built a Refuge on Washington Street

Elmer Goins came from Greensburg, Indiana, where he graduated from high school. After moving to Columbus, he earned his teaching license. He also ran a successful shoe shine business, shining over 1,000,000 shoes during his career—including notable figures like William Jennings Bryan and President McKinley. The income from his shoe shine work fed directly into hotel operations.

Lydia Goins was the primary operator of the hotel, managing daily operations: changing bed sheets, cleaning rooms, and preparing meals. She also raised a foster child named Margaret, who likely helped with hotel tasks. But Lydia’s work extended well beyond hospitality. The hotel also functioned as a rehabilitation center. People who were discharged from the local hospital but couldn’t yet care for themselves came to the Goins Hotel, where Lydia provided baths, food, and walking assistance down the halls. Some residents stayed temporarily while they recovered. Others lived there permanently.

As Roberts described it: “The hotel was not only used to house travelers. It was also used kind of like a rehabilitation center that we have today where people who were discharged from the local hospital and were not able to take care of themselves yet, so they would go to the Goins Hotel. And Lydia provided service for them so that they could get up on their feet and move along.”

Lydia kept detailed records and shared information with Elmer. The two of them built and sustained a business that served their community across multiple needs—lodging, recovery, care, and gathering—in a city that actively worked to keep that business invisible.

Hidden by Design

One of the most striking aspects of the Goins Hotel’s story is how deliberately it was kept from public knowledge–Columbus residents and city officials actively avoided acknowledging its existence.

“It was an eye opener,” Roberts said, “As in most cities, white folks did not want it known that Black people were actually prospering.”

That concealment created lasting consequences for the historical record. Because the hotel operated without public advertising or signage, fewer public records exist. Researching the hotel’s history required Roberts and Kent to work through significant gaps in documentation—gaps that exist precisely because Black success was systematically hidden.

What Banks Wouldn’t Fund, the Community Did

The Goins Hotel didn’t exist in isolation. It was sustained by community-built financial networks that Black residents created because they were locked out of traditional banking. “I found that there was a local group of persons,” Roberts noted, “Who would pool their money together so that one person could further themselves and then they would go on to another person, pool their money so that another individual could start a business.” Elmer Goins was a recipient of funds from Columbus' colored sector of Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization, and this financial safety net helped sustain businesses like the hotel and barbershops on Washington Street.

This is a concrete example of how Black communities built parallel economic systems when they were excluded from the ones that served white residents. Denied bank loans, denied insurance, denied public visibility—and still, Black residents in Columbus created functioning financial networks and thriving businesses.

Eventually, It Was Replaced by a Bank Teller

Lydia Goins passed away in 1945. Elmer tried to run the hotel alone but couldn’t manage it without her. The hotel closed in 1946. The building became rundown after closure, and around 1957, it was torn down to make way for a drive-through window for the bank next door—owned by a white businessman. No records have been found of community pushback against the demolition.

With the building gone and so few public records to begin with, the Goins Hotel's story could have easily been lost. That it wasn't is largely due to the work of Paulette Roberts, who has spent decades collecting oral histories and primary research to ensure that Black heritage in Columbus is documented, preserved, and shared.

Bringing the Building Back to Life

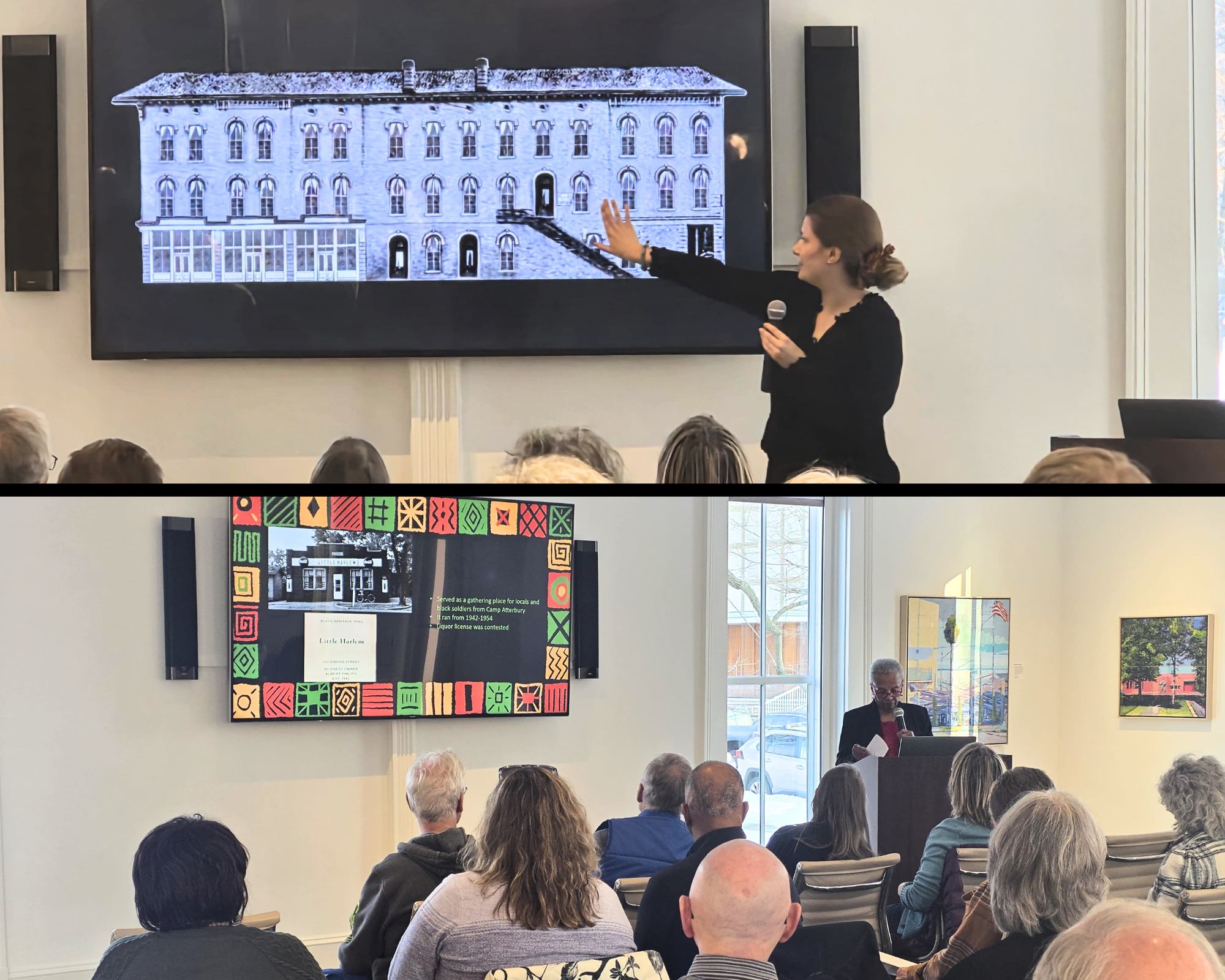

The evening culminated with a special reveal of Cameryn Kent’s visual reconstruction of the Goins Hotel. Until that point, the only existing image was a side view of the building. Kent used that photograph to create an orthographic reconstruction of the hotel’s front facade. For a building with so few public records, the reconstruction gave the audience something concrete to hold onto—a way to see the Goins Hotel as a real, physical place where real people lived, worked, recovered, and gathered.

Kent framed the stakes in architectural terms: being recognized as historic is itself a privilege, because not all history is acknowledged by the larger narrative around it. The Goins Hotel was never granted that recognition. Its story survived because Roberts held onto it for decades—through oral interviews, community conversations, and persistent research—until the broader public was ready to receive it.

Why This History Matters Now

Roberts was clear about what she wanted the audience to take away: “I wanted to provide a kind of comprehensive and accurate understanding of the local history here in Columbus, Indiana. And I wanted them to receive often-overlooked contributions African Americans [made] to the society here in Columbus because it fosters empathy. It puts people in a kind of challenging position, and it honors us as a resilient group of people.”

That accurate understanding requires looking at the specific barriers Black residents in Columbus faced — and what they built in spite of them.

Insurance discrimination, exclusion from bank lending, the active suppression of Black business visibility by white residents and officials—these weren't abstract national forces. They happened in Columbus, Indiana, to specific people, at specific addresses. And Black residents responded by building their own financial networks, their own businesses, and their own community institutions.

When we know how these barriers operated at the local level—specific policies, specific institutions, specific decisions (as Cameryn Kent's secondary source research helped document)—we're better equipped to recognize and dismantle similar patterns today. That's what preservation work like this makes possible.

Roberts closed with gratitude for the family at the center of the story: “We’re just thankful that Elmer and Lydia were smart enough and strong enough to do the work that they set out to do.”

Thank you to Paulette Roberts and Cameryn Kent for their research and dedication to preserving this history, to Landmark Columbus Foundation for partnering on this special edition of Progressive Preservation Talks, to the Columbus Area Visitors Center for hosting, and to Bespoke Events + Experiences for the reception and refreshments.

The Goins Hotel is one stop on the Black Heritage Trail, a self-guided walking tour tracing Black land ownership, businesses, and cultural life in Columbus from the late 1800s through the early 20th century.

About Black History Month Columbus: Black History Month Columbus is about celebrating Black culture, telling the true stories of Black history, and honoring the legacy and accomplishments of the Black community. Join us as we are creating a momentum for community healing through inspiring and educational experiences, and we warmly invite our neighbors from all walks of life to participate ♥